Every product we buy carries an invisible story — one that rarely ends when we’re done using it.

The moment something becomes “waste,” it begins a second life we often ignore: in landfills, oceans, or incinerators.

The problem isn’t just what products are made of — it’s how we think about their endings.

In a circular world, the end of a product’s life isn’t the end at all.

It’s the start of a new cycle — a loop where materials retain value, design anticipates reuse, and waste becomes fuel for creation.

The Linear Trap: Why “End of Life” Became a Blind Spot

Most modern products follow a linear model:

Take → Make → Use → Dispose.

This model has powered convenience for a century — and an ecological crisis for decades.

Globally, humans generate over 2 billion tons of solid waste each year, with less than 20% recycled properly (World Bank, 2024).

The rest — from plastic packaging to electronics — ends up leaking toxins, carbon, and microplastics back into the ecosystems that sustain us.

Products are designed for short-term function, not long-term purpose.

And when something has no defined “afterlife,” it becomes pollution by default.

Designing With the End in Mind

Circular design flips the narrative.

It starts with one simple question: What happens next?

Products are built not for disposal, but for disassembly, reuse, and regeneration.

1. Modular Design for Longevity

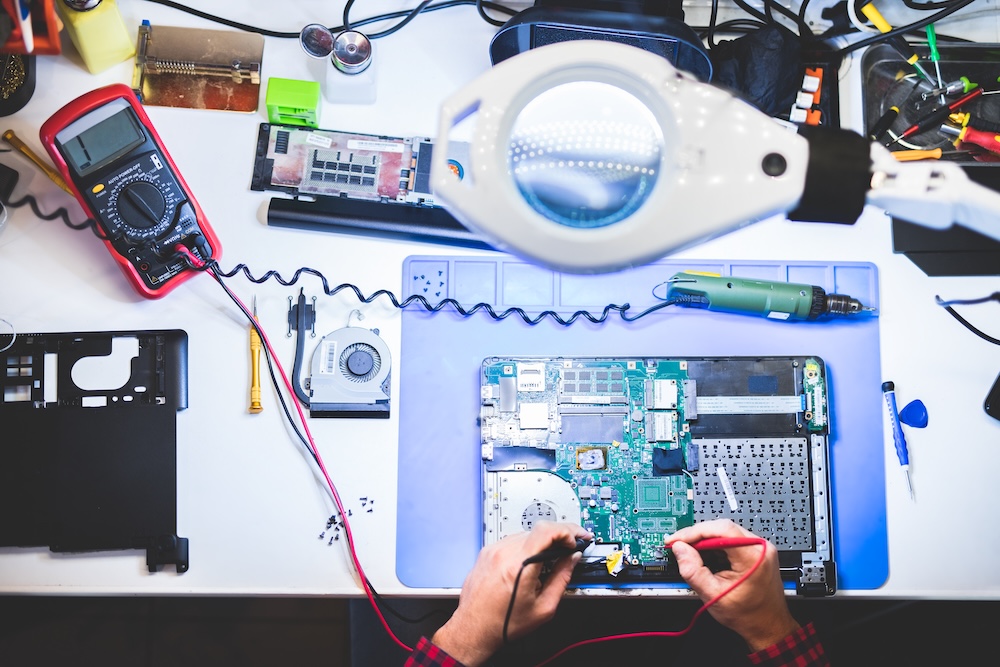

Brands like Fairphone and Framework Laptop are proving that devices can evolve with their owners — each component replaceable, upgradable, and recyclable.

No glued parts. No forced obsolescence.

2. Material Recovery and Rebirth

Furniture, textiles, and electronics are now being designed for reverse logistics — systems that collect and recycle components at scale.

Companies like IKEA and HP are investing in programs where every item can become raw material again.

3. Biodegradable and Compostable Futures

Innovators are developing materials that safely return to the earth — like mushroom mycelium packaging, algae-based bioplastics, and natural fiber composites.

In nature, waste doesn’t exist — everything transforms.

The Business Case for Lifecycle Thinking

Extending product lifecycles isn’t just ethical — it’s economical.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates that adopting circular design could unlock $4.5 trillion in global economic benefits by 2030.

Here’s why:

- Lower material costs through reuse and recycling.

- Customer loyalty through take-back and repair programs.

- Regulatory resilience, as governments tighten waste laws and reward circularity.

Circular models turn waste management into value creation.

The Emotional Lifecycle: Why Consumers Are Key

Circularity fails if people still buy, discard, and replace without thought.

That’s why companies must design not just for function, but for connection.

When a product tells a story — of care, craftsmanship, and continuity — we treat it differently.

We repair it, we share it, we pass it on.

The emotional bond extends its life as much as the engineering does.

Rethinking Ownership

The next evolution of lifecycle thinking isn’t about buying more — it’s about accessing better.

From rental models to product-as-a-service systems, consumers can enjoy the benefits of goods without the burden of ownership.

When items are returned instead of discarded, their materials continue the cycle — turning every user into a steward.

Final Thoughts

Every object has potential energy — not just in how it’s used, but in what it can become.

When we design, buy, and live with the end in mind, we begin to rewrite the story of consumption itself.

In nature, endings are illusions.

Everything feeds something else.

So should the things we make.

Reader Interactions